Significant Operations

This section contains significant/historical events or other items of interest involving USAF helicopters.

Search and Rescue in Southeast Asia, 1961-1975 (Read Story)

Guyana Contingency 20 - 29 Nov 78:

Three 55th ARRS HH-53s (73-1649/73-1651/73-1652), one WC-130 and two HC-130s, deploy to Guyana following the mass death of 914 persons associated with the Peoples Temple religious sect. ARRS flies 30 sorties between Jonestown and Georgetown and evacuates 903 human remains.

Rescue Operations in the 2nd Gulf War (Read Story - pg 95-102)

SECRET MISSION

The Sikorsky H-19 in Vietnam — 1957

During the first week of May 1954 the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. A truce was signed in Geneva that divided Vietnam in half and recognized Laos and Cambodia as independent.

The United States did not sign the treaty but did agree to respect it. It was soon apparent that the U.S. was providing aid to the anti-Communist Republic of Vietnam in the South led by Premier Ngo Dinh Diem. It also became apparent that Diem was preoccupied with trying to reign over a chaos of racketeers, mobsters, and religious sects---all fighting each other over territorial control.

With the departure of the French, the instability of the sitting Diem government, and the increasing American involvement came the realization that the U. S. military had very little “detailed” knowledge of the territory such as maps.

Coincidentally a U.S. military unit was busily engaged in mapping and correcting the world’s geography. Therefore, the USAF gave the Air Photographic and Charting Service (APCS) a gigantic task to map the world.

In 1956 a visual reconnaissance of the preferred sites was completed along with determining the logistics required to install and support the teams that would be operating the equipment.

Because of the sensitive political turmoil in the area, and because the U.S. did not want to give the impression of having any military involvement the activities of the 1370th Photo Mapping Group was given the classification of SECRET.

Clark AB became the base of operations and from Clark to the coast of Vietnam U.S. Navy LST ships manned by Japanese civilian contract crews were used to provide platforms for launching the H-19 helicopters

Team members went ashore at Qui Nhon the morning of February 23, 1957 to set up the first site. The last Air Force personnel departed Vietnam at 1700 hours, 16 May 1957.

The accurate printed maps that were created were provided for use by the combat personnel who eventually followed the photo mapping crews.

The story was provided by Sid Nanson and was published in the Journal, American Aviation Historical Society/Spring 1996

To read the complete story click here.

A later picture of Charles Givens who is the H-19 pilot mentioned in the story

Photo courtesy of Don Larsen via Bill Lyster

Fellow Rotorhead Ron Smitham was the crew chief on this H-21

Largely because of American military assistance, the helicopter section of the VNAF was experiencing a critical pilot shortage in late 1962. Under the Military Assistance Program (MAP) a total of 48 helicopters (H-19 and H-34) were projected for the VNAF by 1 July 1964.

To accomplish the task of training VNAF personnel, the USAF either brought the Vietnamese to the CONUS or it sent Americans to Vietnam to train the Vietnamese in their own country. Superficially, it would seem more efficient to send a small number of American instructors to train a large number of Vietnamese students than to send those same students to the CONUS.

There were political advantages and one of the desiderata of training conducted in the CONUS was the exposure of foreign students to democratic ideals and the “American way of life”. By 1962 due to the deteriorating military situation the political and cultural advantages of CONUS training had to be sacrificed for the greater efficiency of “in-county” training.

On 8 September 1962, CINCPAC sent a message to HQ USAF requesting that “all feasible steps” be taken to alleviate the current pilot shortage of the VNAF. To expedite this training program, CINCPAC asked HQ USAF to get an ATC team “on the road without delay”.

An ATC survey team visited Vietnam from 23 September to 7 October 1962 to study the various possible ways of training VNAF helicopter pilots in that country.

They recommended an FTD be established in Vietnam to provide helicopter and mechanic training. They believed this was the only way to “eliminate the need for USAF Forces serving in any air combat counterinsurgency operations”.

The survey team recommended the FTD be “in Vietnam by 1 January 1963, with training starting 1 February 1963.

In November 1962, HQ USAF approved the team’s recommendations and directed ATC to deploy an FTD to Vietnam to conduct H-19 helicopter training for the VNAF.

FTD 917-S was organized on 3 December 1962 with an authorized strength of 12 officers and 47 airmen drawn from ATC resources. Most of the officers and airmen left the CONUS on 11 January 1963 and arrived in Vietnam the next day. The detachment became operational and began training on 11 February 1963.

Led by Col. Jimmy Hamill, instructors were taken from Stead and other ATC units to began VNAF helicopter pilot training in H-19B helicopters.

The training was conducted on 8 H-19B helicopters. Three were already available at Tan Son Nhut Airfield in Saigon, while the remaining five were in flyable storage at the VNAF Bien Hoa Depot.

With the success of the training and at the urgent request by the VNAF for expansion of the training program, CINCPAC requested and was approved to add 11 officers, 31 airmen, and 9 helicopters.

On 17 June 1963, ATC transferred responsibility for FTD 917-S from Sheppard to the 3635th Flying Training Group (Advanced) at Stead AFB Nevada. FTD 917-S was inactivated and FTD 917-H was designated and organized at Saigon to take its place. The reason for the change concerned the unit’s primary mission of pilot training; it was reassigned to a “compatible ATC flying training organization”.

After graduating its first class of helicopter pilots and while beginning to train its second class the FTD also undertook to train a class of helicopter mechanics. The first mechanics’ class began on 1 July 1963 with 30 Vietnamese students.

A major problem facing the FTD was the inadequacy of its logistical support. Once deployed to Vietnam the detachment found itself short of aerospace ground equipment, hand tools, and spare parts. This poor situation continued through 1963.

By February 1964, through controlled cannibalization, coupled with the improvement of the logistical support the supply problem was reduced to only one aircraft out of commission because of parts. (James O. Smith stated he recalls one particular day sixteen aircraft were in the air)

Although the detachment’s supply situation had improved early in 1964, it continued to have logistical difficulties. The detachment had only six aircraft in commission in early July 1964. An urgent action technical order required that the helicopters’ main rotor head pitch control rods be radiographed. Eighteen of the pitch change rods were not affected by the urgent action technical order.

This procedure was not available in Vietnam so the rods had to be shipped to Air America in Taipei, Formosa. The maintenance personnel met the challenge and kept the six remaining aircraft flying throughout this period.

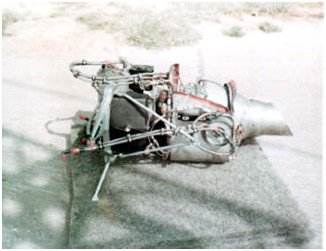

On 16 June 1964 aircraft 53-4454 crashed on take off. (James O. Smith and Dick Kuenzli both have stated it was the result of engine failure)

Personnel rotation presented the detachment with another kind of problem. Sheppard AFB intended to rotate the original complement of detachment personnel in monthly increments beginning in November 1963 and continuing through April 1964, extending the tours of some of the airmen to as long as 15 months. The detachment commander protested the inequity of this program and urgently requested that a more equitable rotation plan be formulated that would provide a minimum period of disrupting concentrated training programs. By October 1963, the original cadre of officers and airmen was being replaced.

Beginning with class 64A training was accelerated in two ways. The training was extended from 5 to 6 days and the flying time per student was increased from 45 minutes to a full hour. These procedures eliminated several issues.

When 26 student pilots graduated on 18 July 1964 that brought the total to 95 pilots trained by the detachment. The detachment also trained 92 mechanics during its 19 months in Vietnam.

Its mission accomplished, the detachment prepared to go home. On 20 August 1964, HQ ATC inactivated FTD 917-H at Saigon.

The FTD under its earlier designation received the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award for the period 12 January to 14 June 1964.

The 3638th Flying Training Squadron (Helicopter) at Stead received the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award for the period of 1 March 1962 to 1 March 1963.

The United States Military Assistance Command Vietnam recommended the FTD for the Air Force Outstanding Unit Award for its performance throughout its period of deployment in the Republic of Vietnam.

Overall the detachment was cited as having contributed significantly to the operational capability of the Vietnamese Air Force.

Click here to view photos in our Flickr gallery!

Note: Former members of this unit are attempting to recall the tail numbers of the 17 H-19 assigned.

The tail numbers identified as of this posting are: 52-10993, 51-3967, 52-7494, 52-7505, 52-7598, 53-4454 and 53-4463. These have been identified through various pictures of that time.

Aircraft 53-4454 crashed while in the unit.

Anyone having any information on the remaining 10 helicopters please contact us.

Air War Korea, 1950-1953

3rd ARS Prepares Casualty for Evacuation

Preparing a casualty for evacuation to a hospital in a 3rd ARS H-5. During the Korean War, men of this unit (later designated a group) earned more than 1,000 personal citations and commendations. (U.S. Air Force photo)

During the Korean War, the increased use of helicopters on rescue missions became a dominant factor in saving lives. By the war’s end, ARS crews were credited with the rescue of 9,898 United Nation’s personnel; 996 were combat saves.

Maintenance personnel with an H-5A on Cho-Do Island, located just off the North Korean coast, 50 miles north of the 38th Parallel, in 1952. Rescue aircraft and a ground control intercept radar facility occupied the island despite the nearness to the enemy mainland. (U.S. Air Force photo)

To commemorate the Korean War, the US Air Force Historian commissioned Air Force Historical Research Agency to compile a chronology of significant events in USAF's operations. The result was "The US Air Force's First War: Korea 1950-1953," edited by A. Timothy Warnock.

A condensed version may be viewed at https://www.airforcemag.com/article/1000korea/

The following helicopter related items have been extracted from the condensed version.

1950

June 25: North Korea invaded South Korea.

Sept. 4: In the first H-5 helicopter rescue of a downed US pilot from behind enemy lines in Korea, at Hanggan-dong, Lt. Paul W. Van Boven saved Capt. Robert E. Wayne.

Oct. 10: A 3rd ARS H-5 crew administered, for the first time while a helicopter was in flight, blood plasma to a rescued pilot. The crew members received Silver Stars for this action.

Oct. 21: UN forces from Pyongyang linked up with the 187th paratroopers in the Sukchon and Sunchon areas. H-5s of 3rd ARS evacuated some 35 paratroopers in the first use of a helicopter in support of an airborne operation. H-5s also evacuated seven American POWs from the area.

Dec. 23: Three H-5 helicopter crews with fighter cover rescued 11 US and 24 South Korean soldiers from a field eight miles behind enemy lines.

1951

Feb. 13-16: H-5 helicopters delivered medical supplies to the troops and evacuated more than 40 wounded.

March 24: For the first time, Far East Air Forces (FEAF) used an H-19, a service test helicopter, in Korea for the air evacuation of wounded troops. The H-19 was considerably larger and more powerful, with greater range, than the H-5s.

March 31: The 3rd ARS used the H-19 to retrieve some 18 UN personnel from behind enemy lines, the first use of this type helicopter in a special operations mission.

April 17: An intelligence operation behind enemy lines resulted in the recovery of vital components of a crashed MiG-15. In Operation MiG, a YH-19 helicopter transported a US and South Korean team to the crash area south of Sinanju. Under friendly fighter cover, the party extracted MiG components and samples and obtained photographs. On the return flight southward the helicopter came under enemy ground fire and received one hit. The successful mission led to greater technical knowledge of the MiG.

April 18: H-5 helicopters from the 3rd ARS evacuated 20 critically wounded US soldiers from front-line aid stations to the nearest field hospital. Five of the 10 sorties encountered enemy fire.

April 24: On separate pickups, an H-5 helicopter from the 3rd ARS rescued first the pilot then the navigator of a downed B-26 near Chorwon, about 15 miles north of the 38th parallel, in the central sector. The navigator, suffering a broken leg, had been captured by two enemy soldiers. But he managed to seize a gun belonging to one of the enemy, causing them to run for cover. Friendly fighters kept them pinned down, while the helicopter made the pickup.

April 30: , two H-5 helicopters each picked up a downed UN pilot behind enemy lines. Small-arms fire damaged one helicopter.

May 5: An H-5 helicopter from the 3rd ARS rescued a downed F-51 pilot north of Seoul, encountering small-arms fire in the area.

May 8: Another H-5 helicopter picked up two US soldiers north of Seoul, encountering small-arms fire in the area.

May 19: An H-5 helicopter rescued a downed F-51 pilot southwest of Chorwon in the central sector, sustaining damage from small-arms fire during the pickup

Sept. 10: South of Pyongyang a 3rd ARS H-5 helicopter, with fighter escort, rescued F-80 pilot Capt. Ward M. Millar, 7th FBS. He had suffered two broken ankles during his ejection from the jet but escaped after two months as a prisoner and then evaded recapture for three weeks. The helicopter also brought out an NKA sergeant who had assisted Millar, delivering both to Seoul.

Oct. 25: In an unusually effective close air support strike, F-51 Mustangs inflicted approximately 200 casualties on enemy troops in the I Corps sector. Enemy small-arms fire hit a rescue helicopter picking up a downed UN pilot. The H-5 made a forced landing in enemy territory. The next day, two other H-5s hoisted all four men to safety from the mountainside where they had hidden from Communist troops during the night.

1952

Jan. 25: A helicopter rescued a downed airman, near the coastline of the Yellow Sea, while F-84s strafed enemy troops in the area. Escorting F-86s destroyed three MiG-15s during the pickup.

Jan. 26: A rescue helicopter, behind enemy lines near the coastline of the Yellow Sea, received small-arms fire while rescuing an F-84 pilot, Capt. A.T. Thawley.

March 27: A helicopter crew, learning that Chinese troops had captured a downed US pilot near Pyoksong, made several low passes, enabling him to escape. While one helicopter crew member fired at the Chinese soldiers with a rifle, others lowered a hoist and rescued the pilot.

April 28: An H-19 helicopter of the 3rd ARS picked up a downed Royal Netherlands air force Sea Fury pilot. It was the second time in three weeks that the same pilot had been picked up by a 3rd ARS helicopter.

May 23: an H-19 helicopter from 3rd ARS flew most of a sortie on instruments and picked up a downed Marine Corps AD-2 pilot-one of the first instances of a primarily instruments helicopter rescue.

June 4: An H-19 helicopter of 3rd ARS picked up a downed British pilot, encountering automatic weapons fire during the rescue.

June 9: A 3rd ARS H-19 helicopter picked up a downed UN pilot, encountering moderate small-arms fire en route.

July 30: Following extended heavy rains, helicopters of the 3rd ARS carried approximately 650 flood-stranded US military members and Koreans to safety. Flying more than 100 sorties, five large H-19s transported some 600 evacuees, while two H-5s carried the rest. In the I Corps sector, two H-5s flew more than 30 sorties to rescue 60 flood-stranded Koreans and US soldiers.

Sept. 4: An H-19 from the 3rd ARS rescued a downed fighter pilot and two crewmen of a USN helicopter, which had lost power and crashed in the water while attempting to pick up the pilot.

Oct. 12: An SA-16 pilot, 3rd ARS, participated in two rescues within 30 minutes and more than 100 miles apart. After directing a helicopter pickup of a downed Sabrejet pilot, the SA-16 pilot landed in the Haeju Harbor and, while overhead fighters suppressed ground fire from the shore, picked up from a dinghy a 69th FBS pilot who had parachuted from his burning F-84.

Dec. 27-31: The 581st Air Resupply and Communications Wing (ARCW) flight of four H-19 helicopters at Seoul flew several experimental agent-insertion sorties into enemy territory for covert and clandestine intelligence activities.

Read more on the 581st ARCW by clicking here

1953

Feb. 28: Third Air Rescue Group received two new and larger H-19 helicopters. MATS C-124s had flown the dismantled helicopters directly from the factory in the US to Japan, where they were assembled and test-flown before being ferried to Korea.

May 18: An H-19 helicopter rescued two members of a B-26 crew 20 miles inside enemy territory by using tactics presaging those of later conflicts. The helicopter scrambled from its base and flew to a small island off the Haeju Peninsula to await fighters to clear the path to the downed airmen. Penetrating enemy territory at 5,000 feet, the helicopter followed the fighter pilots' directions until it located the survivors who were signaling with a mirror. After the survivors set off a flare to indicate wind direction, the helicopter landed and rescued them, staying on the ground for approximately 30 seconds.

CH-3E 65-12790 on display at Hill AFB Museum.

CH-3C/E MARS Recovery Aircraft:

63-9687

63-9690

64-14223

64-14226

64-14228

65-5690

65-5696

65-12788

65-12790

View photos of the Buffalo Hunters in our Flickr gallery.

The 432nd Drone Group operated out of Davis-Monthan utilizing the CH-3E MARS equipped aircraft. The MARS mission was also utilized during the war in Southeast Asia. Click here to view some pictures taken at the March 1977 Open House at Davis-Monthan.

The 6514th Test Squadron of the Air Force Systems Command was activated at Hill AFB on 1 July 1973 as a detachment of the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC) at Edwards AFB, California. The unit was responsible for the testing of remotely-piloted vehicles over the Utah Test and Training Range.

The 6514th Test Squadron of the Air Force Systems Command was activated at Hill AFB on 1 July 1973 as a detachment of the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC) at Edwards AFB, California. The unit was responsible for the testing of remotely-piloted vehicles over the Utah Test and Training Range.

MEMORABLE MISSION OF HARVEY METZLER

I was assigned working MARS at DaNang in 68. I Flew 59 missions, 1/2 of them were in NVN. Yes there are plenty of stories to share. One quick one. The Bug aborted early, went into the chutes just off of Tiger Island NVN. It became a race to try and get it before it went into the water. We were at orbit 10K feet and many miles away. We went into a high speed decent with our poles deployed (scary) , max speed should be 50kts. We did get up over 70. The catch was done with the bug about 20 ft from the water. Then with it half way to stow position the winch stopped. We flew for the next hour with the bug over 100 feet below us. What I never can forget was the radio on guard calling "Bandits" heading south from Squid and Oyster, the 2 biggest MIG bases. But we made it back and delivered the Bug intact. We always flew twice a day on these. Sometimes they went clean and neat.

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE FROM JIM BURNS

I was part of a crew picking up a drone recovery bird from Edwards, AFB and ferrying it to Tyndall (I think this was in 1972) and got to make two MARS flights. The above picture shows the winch box mounted on the cabin floor and the 'snatch' poles that were stuck out the rear of the cabin. Here's what else I think I remember about the system. The winch box was mounted over a hole in the cabin floor and the recovery cable was strung along the bottom of the hull and attached by a break away rope or string or something to the end of the poles. There was a grappling hook on the end of the cable. In flight the poles were extended out and down from the back of the cabin and the snatch cable and grappling hook trailed below the chopper, strung between the two poles. The pilot positioned himself above the drone altitude and when the drone's recovery main chute and drag chute deployed the H-3 would dive down from above it and fly right over the top of the chute where the trailing grappling hook would snag the chute and capture the drone. Once the drone had been 'snagged' and stabilized below the chopper, then the winch cable would be reeled in to bring the drone to about 20 feet below the chopper. Then it was flown to a soft landing and released by the CH-3.

The drones weighed between 2,000 to 2,500 pounds and I don't take a lot of imagination to know how the CH-3 might react when it's diving on a drone at about 100 knots ,or so, and it snags into a couple thousand pounds of weight swinging like a pendulum at the end of a very long cable. Thank goodness for the hydraulics that slowed down the impact of the snag. I would imagine that if the cable was fixed without a chance to reel out and slow down the grab that it would yank the chopper out of the sky.

My memory of the these missions is of the steep dive to snag the chute, then the sudden stop once the drone, with all it's extra weight was caught, then the H-3 beginning to fly again, then the winch procedures. Maybe it was because I was more or less a 'tourist' on these two missions, but this just seemed like a hell of a way to make a living!!!.

COMMENTS FROM BOB BUTTERFIELD

Jim B, your description of a drone recovery is correct. To clarify further, the rope that was connected to the cable was attached to the poles by duct tape (pretty Hi-tech). It was a rigging that had three hooks, one at the end of each pole and a "Flying Hook" that hung in between. When contact was made with the drag chute, the hooks and rope pulled free of the poles, the winch fed out cable and hydraulics slowed the feed out. That was the moment that you heard a definite "Rotor Droop" as the sudden weight slowed the rotors and there was a rapid decent. Not a comforting sound. Once the drone was reeled in and stowed beneath the H-3, it was a pretty uneventful trip to the drop zone, where the drone was lowered to the ground and the rope was cut by the WO. Other than the few moments after a "Capture", the missions were fun. We always used two choppers on a recovery mission just in case the Primary Bird missed the drag chute or had a "Tear Through".

RECOVERY SYSTEM

Info courtesy of Dave Matthews - Provided by Kelly Day

1. Recovery began at mission altitude with a command that could be initiated internally or via remote control. If the vehicle was configured for test range flight, range timer logic would command recovery to prevent annoying the FAA or citizens in case remote control was lost for a pre-set time. In operational configuration recovery could only be commanded remotely.

2. The recovery sequence began with deployment of the drag chute and shutoff of the engine. The drag chute, in the cap at the very end of the chute can, is an 8 foot ribbon-type parachute. The cap is held on by two screws; internal initiators fire to shear the screws and aerodynamic forces pull the cap free and extract the drag chute. The drag chute is initially reefed by a line that passes around the base, and a pyro-activated cutter cuts the reefing line after the initial shock of opening. The engine is shut down by closing the main fuel solenoid and starving the engine. When recovery was commanded, unneeded systems were removed from the DC bus to avoid an excessive drain on the recovery battery.

3. As the drone fell from altitude in drag, it would rapidly pitch over, as the flight controls were disabled.

4. As the vehicle passed through 15K feet, barometric switches passed power to the main chute can. The can is held in place by three disks, attached to plungers internal to the can. When recover power is applied, initiators fire to retract the plungers and rivets holding the outer disk are sheared, releasing the can. Since the drag chute is attached directly to the aft end of the can, the main chute can is positively pulled from the aft bulkhead. The parachute line passes along the upper right side of the drone to two attach points, both fore and aft of the center of gravity. As the can is pulled free, tension on the line pulls the main chute and then the engagement chute out of the can. The can and drag chute then fall free and play no further role. The main and engagement chute begin to inflate, but both are reefed to prevent excessive opening shock. Once fully inflated, the main chute is a 100 foot cargo chute and the engagement chute is a 28 foot special purpose chute. The engagement chute has a bridle affair sewn into the canopy, and this bridle is part of a 10,000 pound load line that is loosely attached to the main chute directly opposite the aiming gore on the main chute; the load line then passes outside the main chute risers to a handclasp affair that is also the attach point for the main chute risers. At the same time the chutes are deployed, the dump valve opens under the main fuel tank, ensuring that any excess weight is removed.

5. Normal recovery sequence involves the helicopter flying over the engagement chute at about thirty knots, with the same rate of descent (1000 fpm) as the drone package. The CH-3 (or -53) has two poles extended below the aft cargo deck, with a treble hook suspended between them. Any of the three hooks will tear through the fabric of the engagement chute canopy, and catch the engagement bridle. At this time the engagement hooks pull free of the poles. As the chopper continues its forward motion, it pulls the load line free of the main chute, and takes more and more of the drone’s weight (between 1700 and 2700 pounds, depending on the drone type). The lines on the chopper terminate at a steel cable that runs underneath and into a well cut in the floor to a floor-mounted winch directly under the main transmission and rotor blades. As the weight increases, the winch initially allows rapid unwinding of the winch reel to avoid shock loads. As the rpm of the reel increases, a hydraulic brake begins to attempt to slow and then stop the winch. Load sensors in the winch mechanism will normally stop the descent of the drone after about 200 feet. At the same time the weight is being transferred to the load line, the load line is also transferring weight to the side of the handclasp away from the part that is suspended by the main chute. When most of the weight has transferred to the load line, a rivet fails in the handclasp, releasing the main chute line. The main chute then falls free and of course behind the drone/helicopter formation. In SEA the main chute then became a prize for anyone who found it. In some cases, the chute fell to the ocean and was lost. When the handclasp operates, a micro-switch is closed in the handclasp, and a 5 foot parachute attached to the aft bulkhead is release by a reefing cutter, stabilizing any drone oscillations. As soon as the drone is stable, the winch reels in all but about thirty feet of the load line. The airspeed of the helicopter is restricted until the drone reaches this stowed condition. When the drone is brought back to the operating base, the winch then lowers the drone onto a fuel bladder that is filled with water. The load line is then cut and the drone belongs to maintenance.

6. A water recovery sequence begins in the same manner, up to the point of engagement. Occasionally, the hooks will tear the engagement chute without catching a bridle point. This is known as a ‘tear through’ and usually results in enough damage to the engagement chute that it no longer flies above the main chute. When this happens, the chopper crew is helpless and must wait for ground/water impact to make the recovery. If the drone lands in water, exposed contacts on a salt-water switch close a circuit that fires an initiator below the handclasp, separating the parachute system from the drone. The salt water switches also cause the dump valve to close, preventing water from filling the main tank. The drone has a spring on the forward bridle attach point that lifts the riser about two feet. The chopper crew has a hooked pole that allows them to manually attach the engagement hook to the bridle and they can then lift the drone from the water or ground.

"THE FLYING OIL SLICK" -- Ops officer on the left Mark Tarbet, Lt. Ira Barilleaux, 2 Uknown w/ John Dorgan on Right

SAC crew E-85 in 1970 -- From left, Dwayne Feltcher P, Rick Davis, CP, Johnny Johnson FE, John Dorgan, FE/WO.

For pictures of an actual drone recovery, visit our photo gallery.

LT-RT-TEXAS INST EMP, A1C KOLBE, CAPT DAVID FRASER, 1Lt NEIL McCUTCHAN & TEXAS INST EMP

We flew one of our helicopters to Hattiesburg from MacDill. We would hover over a spot for quite a while. If I remember right the package was designed by Texas Instruments. Their techs would fly with us to take measurements. PHOTOS COURTESY OF NEIL McCUTCHAN

H-19B L-R (Unk, Hubertus_Singel_Kuenzli)

The CLUI Land Use Database

Site Name: Salmon and Sterling Nuclear Test Sites

CLUI LUDB#: MS3126

Category: Nuclear / Radioactive

Description: Two nuclear detonations performed in a subterranean salt dome formation in Mississippi, as part of a 1960's Atomic Energy Commission Test. The test program, called Project Dribble, called for creating an underground cavity, using a nuclear bomb to do so, then later detonating a second nuclear device, as well as two gas explosives, inside the cavity. The purpose of the test was to measure the patterns of the shock waves generated by the explosions, to be better able to detect and calculate yields of similar underground tests that might be performed by the USSR. The first detonation, to form the cavity, code-named Salmon, took place in 1964 using a 5.3 kiloton bomb, placed at the bottom of a sealed 2,710 foot shaft. The second nuclear blast, a relatively small 0.38 kilotons yield shot code-named Sterling, was exploded within Salmon's 110 foot diameter cavity more than two years later. The two conventional explosives shots were performed in 1969 and 1970.

Location: 28 miles SW of Hattiesburg, MS, four miles NE of Baxterville.

Web Links:

https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/SalmonFactSheet.pdf

http://clui.org/ludb/site/salmon-and-sterling-nuclear-test-sites

https://mashable.com/feature/mississippi-nuclear-test

https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/nuclear-blasts-in-mississippi

Taking a H-19 helicopter from Wright-Patterson AFB, SSgt Bob Singel and I along with two pilots and I can’t remember their names were sent TDY to Mississippi. It was highly classified and they didn’t let us know until we got there what we would be doing. As it turned out we were involved in the testing of an A-bomb blast down in the earth where there was a large concentration of salt. The theory was they could use one tenth of an A-bomb down there and the heat and explosion would create a chamber made of salt that could be used to store fuel.

What they actually stored down there is anybody’s guess, remember this was 1964 time period and they didn’t tell much back then. Well it was supposed to last three days and those three days turned out to be forty days if I remember correctly. If it wasn’t something wrong with the technical side of it, it was weather related. Our mission was to keep people out of the area around ground zero.

There were H-19s, H-21s and H-43s involved in this mission, each assigned an area to keep cleared. The day they actually fired the damn thing I was on the ground. Singel and I took turns on missions, he was up and I was down.

They had a place where we kept the birds about 15 miles away from ground zero. That’s where I was when it came over the loud speaker that it was going to be a go. They said we should bend our knees because this was going to be a large shock. I thought yeah right, well let me tell you it was like jumping out of a H-19 about 20 feet in the air and landing on a concrete runway and then bouncing for about 20 seconds. Man did that hurt and my knees are still paying for not listening to what they said.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it. (Dick Kuenzli)

PLUMBBOB PROGRAM

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

"I feel impelled to speak today in a language that in a sense is new--one which I, who have spent so much of my life in the military profession, would have preferred never to use. That new language is the language of atomic warfare."

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment and information to schools, hospitals, and research institutions within the U.S. and throughout the world.

Subject: SHOTS WHEELER TO MORGAN, The Final Eight Tests of the PLUMBBOB Series

6 SEP - 7 OCT 1957

Helicopter Surveys

SHOT "WHEELER"

6 Sept. 1957, 0545 hrs.

Ninety minutes after the detonation, one H-21 helicopter, with two AFSWC crewmen and two radiological safety monitors, left the airstrip near Camp Mercury and flew a survey mission over the WHEELER shot area and other designated points to record radiation intensities. The survey took an estimated 40 minutes. Crew members wore anticontamination clothing and respirators during the flight. After the mission, the helicopter returned to the helicopter area at Camp Mercury, where aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required. Subsequent surveys were canceled, as discussed in section 2.3. A survey to assess detonation damage, planned for about two hours after the shot, was also canceled (1; 2; 44).

SHOT "LA PLACE"

8 Sept. 1957, 0600 hrs.

After the detonation, one H-21 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two and at least two REECo monitors, left the airstrip near Camp Mercury and flew survey missions over the area to assess detonation damage. Crew members wore anticontamination clothing and respirators during the flight. Following the mission, the H-21 returned to the helicopter area, and aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required. The initial aerial radiological survey team, with an AFSWC crew of two and two REECo monitors, departed from the Control Point helicopter pad at 0733 hours, about 90 minutes after the detonation. After completing the mission, the team returned to the Control Point helicopter pad (1; 3; 45).

SHOT FIZEAU

14 Sept. 1957, 0945 hrs.

After the detonation, two H-21 helicopters, each with an AFSWC crew of two and at least two REECo monitors, left the airstrip near Camp Mercury and flew survey missions over the FIZEAU shot area to assess and record radiation intensities. Another H-21, with an AFSWC crew of two and one REECo monitor, made a damage assessment survey of electrical poles along Mercury highway. An H-21 photography mission was canceled prior to takeoff because it was not needed. After the mission, the helicopters returned to the helicopter area, where aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required (1; 4; 47; 61).

SHOT NEWTON

16 Sept. 1957, 0550 hrs.

One hour after the detonation, one H-21 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two and at least two REECo monitors, left the airstrip near Camp Mercury to survey and record radiation intensities in Area 7 and other non-test areas of the NTS. The helicopter spent about 40 minutes in the test area. Subsequent helicopter radiological surveys occurred on 17 September. Following the mission, the helicopter returned to the helicopter area. Aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required (1; 5; 48).

SHOT RAINIER

19 Sept. 1957, 1000 hrs.

After the detonation, one or two H-21 helicopters, each with at least two AFSWC crewmen and a REECo monitor, left the airstrip near Camp Mercury and flew survey missions over the RAINIER test area to assess detonation damage. Following the mission, the helicopter returned to the helicopter area. Aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required (6; 16; 46).

SHOT WHITNEY

21 Sept. 1957, 0530 hrs.

After the detonation, two H-21 helicopters, each with an AFSWC crew of two and two REECo monitors, conducted aerial radiological safety surveys of Area 2 and other non-shot areas. The helicopters surveyed for about 40 minutes, whereupon they returned to Camp Mercury. Resurveys took place later on shot-day. Two other H-21 helicopters, each with an AFSWC crew of two and REECo radiological safety monitors, conducted a damage assessment survey over the shot area after the detonation. After the mission, the helicopters returned to the helicopter area at Camp Mercury. The aircraft and crews were monitored and decontaminated as required (7; 49).

SHOT CHARLESTON

28 Sept. 1957, 0600 hrs.

After the detonation, one H-19 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two and at least two REECo monitors, conducted a radiological survey over the shot area. Two other H-19 survey missions were canceled because they were not needed. Following the mission, the helicopters returned to the helicopter area. Aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required (8; 50).

SHOT MORGAN

7 Oct. 1957, 0500 hrs.

One hour after the detonation, an H-21 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two and at least two REECo radiological safety monitors, conducted an initial radiological survey of Area 9 and other locations. A second H-21 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two, a REECo radiological monitor, and UCRL project participants, left the Control Point an hour after the detonation to recover project equipment east of Area 9. About two hours after the shot, an H-21 helicopter, with an AFSWC crew of two and REECo radiological safety monitors, conducted a bomb damage survey mission of Area 9. Following the mission, the helicopters returned to the helicopter area. Aircraft and crew were monitored and decontaminated as required (9; 51).

Click here for more information

If you have any information on the Air force helicopter unit that supported this please contact us.

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

"I feel impelled to speak today in a language that in a sense is new--one which I, who have spent so much of my life in the military profession, would have preferred never to use. That new language is the language of atomic warfare."

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment and information to schools, hospitals, and research institutions within the U.S. and throughout the world.

Subject: Projects GNOME and SEDAN, The PLOWSHARE Program

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) established the PLOWSHARE program in June 1957, under the technical direction of the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (LRL).

The program consisted of27 nuclear detonations conducted at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) and other sites in Colorado and New Mexico from 1961 to 1973.

The nuclear tests were all underground, either shaft or cratering shots, and they had yields of no more than 200 kilotons. The PLOWSHARE nuclear detonations were designed to determine nonmilitary applications of nuclear explosives. The primary potential use envisioned was in large- scale geographic engineering, in such projects as canal, harbor, and dam construction, the stimulation of oil and gas wells, ant mining.

This report describes the activities of DOD personnel and other participants in Projects GNOME and SEDAN, the first two nuclear tests of the PLOWSHARE Program.

The PLOWSHARE nuclear tests were conducted from 1961 to 1973 at the Nevada Test Site and other locations. Activities engaging DOD personnel at GNOME and SEDAN included scientific experiments to improve U.S. capabilities in detecting underground nuclear explosions and to determine peacetime uses of nuclear explosives.

2.5 AIR FORCE SPECIAL WEAPONS CENTER ACTIVITIES AT PROJECT GNOME

The Air Force conducted several support missions at Shot GNOME. Available documents suggest that various Air Force units under the operational control of the Air Force Special Weapons Center conducted a security sweep, cloud-sampling mission, cloud-tracking and radiological safety sweep, and support missions.

Project GNOME, a shaft detonation, was fired at 1200 hours Mountain Standard Time on 10 December 1961 at a site 40 kilometers southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico.

Security Sweep

An Air Force H-21 helicopter with a two-man crew made a security sweep of the area in an eight-kilometer radius of ground zero. The helicopter began the sweep two hours before the detonation and concluded it 90 minutes later. The helicopter then moved to a position over New Mexico Highway 128, north of the Control Point, to observe traffic and to ensure that no unauthorized vehicles were in the shot area.

Cloud Tracking and Radiological Safety Sweep

An Air Force H-21 helicopter and crew, likely the same one that conducted the security sweep, conducted a cloud-tracking and radiological safety sweep beginning one minute after the detonation and continuing for two or three hours.

Click here for more info.

If you have any information on the Air force helicopter unit that supported this please contact us.

Subject: SHOTS WHEELER TO MORGAN, The Final Eight Tests of the PLUMBBOB Series

6 SEPTEMBER - 7 OCTOBER 1957

In 1947 when the Air Force became a separate entity there was always disagreement between senior military leaders of who should have control of the air resources. The controversy continued through the years with the Army feeling they should have control of the close air support and tactical airlift as a separate air arm of the Army.

The USAF Tactical Air Warfare Center (USAFTAWC) originated as a result of a U.S. Army request in 1961 for additional air support. Gen. Curtis LeMay, then Air Force Chief of Staff, tasked the USAFTAWC to prove the Air Force could support the Army's need for close air support and tactical airlift more effectively than a separate air arm of the Army. The center's first task was to prepare plans for joint Army Air Force tests and evaluations. Its role expanded to include the general improvement of tactical air in support of ground forces.

In 1964, USAFTAWC proved the Air Force's capability to provide support to the Army during exercises "Indian River" and "Goldfire." As expected, there were shortfalls in equipment, tactics and training. The Air Force broadened USAFTAWC's mission to address these deficiencies and included the acquisition and testing of off-the-shelf equipment items, with emphasis on strengthening the Air Force tactical air capabilities.

Exercise Goldfire I in 1964 featured mass deliveries by C-130s and further use of the low-level extraction methods. A small provisional unit of USAF CH-3 helicopters performed over 600 assault and resupply sorties: the unit’s commander foresaw “a vastly expanded rotary-wing retail air arm working in concert with a fixed-wing wholesale delivery.”

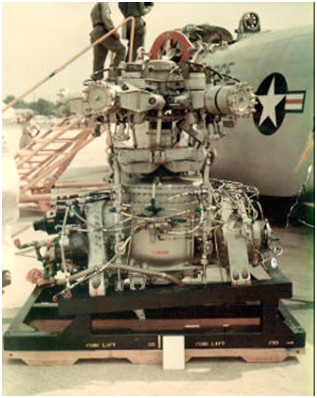

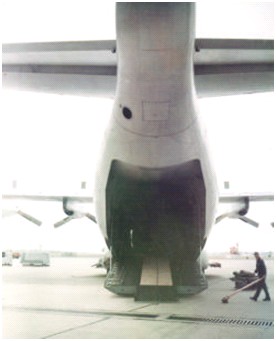

Part of the Air Force requirement to prepare for Gold Fire I was to prepare six CH-3 helicopters for air shipment in a C-133 aircraft. They would be airlifted to another location and reassembled and made ready for the exercise. This all had to take place in a 24-hour period.

The 4488th Helicopter Squadron at Eglin AFB was given the tasking. This was to be a first for airlifting the H-3 helicopter in a C-133 aircraft. The 4488th went Air Force wide and drew in the best helicopter mechanics the Air Force had for this important tasking.

A team of Sikorsky maintenance people traveled to Eglin to demonstrate the procedures for preparing the aircraft, loading and unloading them and reassembling for flight. A handpicked team of Air Force helicopter technicians were trained in the procedures and then later they trained additional personnel resulting in 48 technicians being fully trained for the operation.

Otto Kroger was one of the Air Force’s supervisors involved in this operation and his memories of the activities as well as photos are below.

THE DISASSEMBLING OF CH-3s FOR AIR SHIPMENT IN A C-133

(OTTO KROGER)

This is the story of the first disassembly of CH-3 helicopters for air shipment in a C-133 aircraft. At Elgin AFB FL in 1964 for operation Gold Fire I, a Joint Army & Air Force exercise held in southern Missouri. Our job was to prove to the Army that we could disassemble 6 each CH-3 helicopters and ship them two thousand-miles and reassemble them for mission duty in twenty-four hours. This task was preformed.

To start Sikorsky assembled the required jigs and tools for the aircraft to be made air shipment ready. This total operation was filmed for later training. The first disassembly was accomplished by Sikorsky mechanics with the Air Force observing the operation. Later two TSgts, were selected to train 12 man teams in total disassembly, in crews of three and four men, all trained in more than two or three phases of the operation and could cover each other or help when more manpower was needed in an operation.

Crews were trained for a 12-hour work shift with half-hour overlap for briefing of the new crew. After the project the tools and jigs selected for the job were tested for strength and some were modified. The heavy transmission sling was tested to pick up the whole aircraft. We later used it this way to put the aircraft in a special cradle so the sponsons could be installed easier and safer than doing it with the small jacks.

We had some of the best helicopter mechanics ever assembled in one place for this project. Training of these men was done with the prior filming of the job and hands on training from one aircraft to the next with one crew always watching until they all knew each task. Then they were assigned to three and four men crews each working a special area.

The first set of photos shows the tools & jigs, and the Sikorsky mechanic assembly crew. The box, near the center, in the photo is a hydraulic pump which is attached to the helicopter fuselage loading jig wheels and nose wheel. The pump allows you to raise and lower the fuselage as you enter the C-133 to maintain proper clearance. The blue pump was attached at the rear of the CH-3 and rolled along with the fuselage.

BELOW ARE SOME OF THE SPECIAL TOOLS, SLINGS AND SHIPPING CONTAINERS

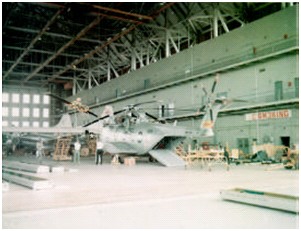

Some of the disassembly was accomplished inside the King Hangar while the majority of it took place outside

as it was expected there would be no hangars available at the deployed assembly location.

THESE NEXT PICTURES ARE SOME OF THE INSIDE PORTION OF THE OPERATION

Sikorsky’s first attempt to load the helicopter was made with the engines and doghouse cowl installed and they discovered there wasn’t enough overhead clearance. After these items were removed the second try went fine.

The first fuselage was moved to the C-133 front bulkhead using the aircraft interior winch, hooked to front gear. Blades were stored inside the fuselage. Transmissions were stored behind first helicopter fuselage and tied down. Now we are ready to load second helicopter fuselage.

Here is how we worked the first crew with the main rotor blade removal and boxing. One man removed the attaching bolts and three men with a blade sling and guide ropes lowered the blades to the ground and put them into a blade-shipping container for safe keeping. The mount bolts were reinstalled in the rotor head for shipment.

While crew 2 was removing the tail rotor blades and boxing them, mount bolts and rotor-head sling went into the blade shipping box for safe shipment. The first crew’s blade bolt remover/installer connected the rotor head sling to the crane as it was jacked up.

Crews 2 & 3 prepared and removed sponsons with strap slings.

Crews 1 & 4 handled putting sponsons on their shipping jigs.

Crews 2 & 3 installed main wheel loading jigs.

Crew 1 installed the hydraulic pump to main wheel jig and nose wheel.

The aircraft is now lowered on to the jig’s wheels

Crew 4 prepares and loosens the tail pylon bolts. With the pylon sling installed the pylon is removed and installed in the pylon shipping jig.

The pylons are mounted in the jig with its mounting bolts and marked with the aircraft tail number.

The crew 1 "bolt removal man" installed the main transmission sling, while crew 3 was preparing the main transmission for removal. The engine drive shafts were removed, tail rotor drive shaft unhooked, and main hold down bolts were removed and all the mount bolts were secured in fuselage mount holes. Now crews 1 & 3 worked together to remove the transmission and secure it in its shipping jig.

We are now down to where the Sikorsky people tried putting the fuselage into the C-133, but they discovered that the dog house cowling and the APU must be removed.

Crew 4 removed the cowling and mounted it in the shipping jig. They removed the APU and starter tube, which were to be shipped in wooden crates.

We can now pull the helicopter safely into the C-133. All loading was done with the C-133 loadmaster supervising.

With one CH-3 fuselage in place next came the two transmissions on their stands and the two APU storage boxes.

The second CH-3 fuselage and then the two tail pylons, doghouse cowling, tail rotor boxes and the four sponsons on the shipping jigs were loaded.

The load is now ready to fly. We left Elgin AFB and flew to the Memphis Navy reserve unit where the re-assembly would take place.

I had come to Memphis the night before and marked the ramp with the six helicopter tail numbers in squares, lined up in two rows to setup our production line assembly for when the aircraft arrived for off loading.

We were housed on station by day or night crew so no one was awakened wrongly. The mess hall was open to us 24 hours.

We did start with a hiccup as we only had one crane for the two lines so we had to share time. We had a small floor crane to put the sponsons and tail pylons on so that helped.

We also didn’t have our special tools and torque wrenches because a C-124 blew an engine and we had to wait till they got another aircraft to deliver them. After 12 hours we were back on schedule.

Now we moved the first two fuselages into the area with the crane between them. First up were the transmissions with two crews inside and out hooking up engine shafts, tail drive shafts, main transmission mount bolts and lines.

Another crew of four men got the tail pylon ready to lift into place and installed the mount bolts and cables inside the tail cone.

Outside the tail rotor blades were installed and bolts were torqued while working off of the maintenance stands. Another two crews worked together getting the sponsons ready to install using the floor crane and slings. The other crane was used to stabilize the fuselage, for safety, while the fuselage was raised and placed on jacks.

The main gear jigs were removed and sponsons installed, mount bolts were installed and torqued. The main gear was lowered and lock pins were installed. The aircraft was then lowered on to its gear and all hydraulics was checked. The aircraft could now roll on its own wheels. We now had crews installing the doghouse cowling and APU system.

Crews were now un-boxing the main rotor blades and readied them on the blade sling to be installed. We now had another rented crane, so we moved the aircraft forward and installed the blades one ship at time and then moved them out on the flight line for final inspection and ground run-up checks (blades were tracked).

Then the aircraft were turned over to flight test crews. All write-ups from the test flight were fixed and signed off. The aircraft were then turned over to combat ready flight crews to fly to Missouri for the joint exercise.

See photos below:

CH-3C 63-09689

1964 -- In a night operation, a U.S. Air Force CH-3C helicopter hovers with a cargo load before airlifting it to a forward location. The operation was in support of Joint Task Force Ozark during U.S. Strike Command's Exercise Gold Fire I. The downdraft from the whirling blades raised a cloud of dust and chaff around the rotor-bladed aircraft. (U.S. Air Force photo).

CH-3C 63-09689 & 63-09684 in background

CH-3C helicopter 1964 -- FT. LEONARD WOOD, MO -- A U.S. Air Force CH-3C helicopter airlifts a 106mm recoilless rifle mount on a U.S. Army jeep from a rear area into the "battle zone" in support of OZARK forces. This action was part of a simulated "battle" between the OZARK and SIOUX forces during U.S. Strike Command's Joint Exercise GOLD FIRE I, held in southern Missouri. 10 November 1964. (U.S. Air Force photo).

57-2728 USAF Museum |

|

57-2729 |

President Eisenhower is the only sitting President the Air Force transported by helicopter.

During a civil defense drill, President Dwight D. Eisenhower rode in his personal limousine while cabinet members flew in a helicopter and arrived at the bunker far sooner than the president did. This sobering outcome sparked the search for a suitable helicopter to whisk the Chief Executive to safety.

In 1957, President Eisenhower began asking about the use of rotary aviation as a means of presidential transportation. Because of a difference of opinion between the Air Force and the Navy, President Eisenhower decided to leave the decision with the Secret Service.

Until 1955, the Secret Service had refused to allow the President to fly in any aircraft equipped with less than four engines. After Secret Service flight rules eased, a single-engine helicopter appeared very convenient for presidential transport because it could operate from the White House lawn.

They concluded that helicopter travel would be as safe a method of transportation as the traditional wheeled motorcade, and The Air Force was instructed to purchase two Bell UH-13-J helicopters for use by the President. The White House also contacted Sikorsky to design a helicopter for the President's personal use.

These new aircraft were nearly identical to the standard production Ranger configured as a commercial executive transport. Bell only added two new features to the presidential version; all-metal rotor blades to increase the helicopter's useful load and special tinting to the huge Plexiglas nose bubble to reduce glare and heat.

"Operation Alert" began on July 12, 1957, and by mid-afternoon, Eisenhower had become the first U.S. President to fly on board a helicopter. Major Barrett flew the UH-13J bearing serial number 57-2729. He carried President Eisenhower and a Secret Service agent to Camp David. The President sat in the right rear seat but leaned against a special armrest installed for him on the center seat. He also used a special footrest.

The second UH-13J, serial number 57-2728, carried the President's personal physician and another Secret Service agent. Both helicopters were based at National Airport, along with the other presidential aircraft.

This was the start of almost weekly flights to either Camp David or to Ike's Gettysburg farm. Flights to the farm first flew to Camp David, where a strobe light placed in top of the barn at Gettysburg guided the helicopters to the farm.

The two Air Force UH-13J aircraft were designated to fly the president to his Super Constellation airplane at National Airport (D.C.), to Camp David (MD) and to his farm in Gettysburg (PA).

After their White House assignment, the two UH-13Js were used to transport high-ranking Department of Defense personnel. In July 1967 both were transferred to the Smithsonian. The helicopter that President Eisenhower used to make the first helicopter flight is at the Paul E. Garber facility. The other UH-13J is on loan to the Air Force Museum Dayton, Ohio.

Integrity, Honor, and Respect

Some of the best things cannot be bought, they must be earned

©2023 USAF Rotorheads All Rights Reserved | Financial Statement